CNN's blurb about the raid HERE

Front Page Style Section, August 19th 1995..

Copyright 1995 The Washington Post

WP 19.08.1995 06:00

Click for full size image

Click for full size image

By Marc Fisher Washington Post Staff Writer

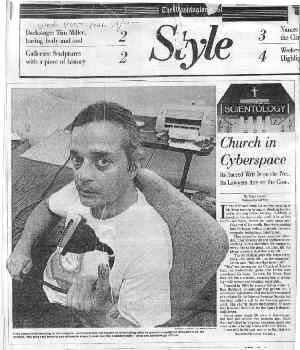

It was 9:30 and Arnie Lerma was lounging in his living room in Arlington, drinking his Saturday morning coffee, hanging. Suddenly, a knock at the door --

who could it be at this hour? -- and

boom, before he could force anything out of his mouth, they were pouring

into his house: federal marshals, lawyers, computer technicians, cameramen.

They stayed for three hours last Saturday. They inventoried and confiscated

everything Lerma cherished: his computer, every disk in the

place, his client list, his phone numbers. And then they left.

"I'm one of those guys who keeps everything -- my whole life -- on the

computer," Lerma says. "And now they have it all." "They" are lawyers

for the Church of Scientology, the controversial group

that Lerma once considered his home, his rock, his future. Now they call

him a criminal, accusing him of divulging trade secrets and violating copyrights.

Founded in 1954 by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, Scientology has

grown into a worldwide organization that has been recognized as a religion

by the Internal Revenue Service but has been called a cult by the German

government. The church claims membership of more than 8 million; its

critics say the figure is dramatically lower.

Lerma spent nearly 10 years in Scientology. But that was almost two

decades ago. Since then, he's lived in Virginia, designing sound and video

systems for nightclubs and other clients.

It was only in the past year or so that Scientology and Arnie Lerma have

gotten reacquainted, and this time Lerma has a different view of the church:

He considers it a dangerous cult, a corrupt organization dedicated

to brainwashing its followers. To convince others of this view, Lerma used his

facility with computers to

distribute some of Scientology's most sacred texts, documents he says were

obtained from a public court file in Los Angeles. In recent months, Lerma

and others have placed dozens of these documents on the Internet, in a

discussion group called alt.religion.scientology, a busy place in

cyberspace where Scientology critics and adherents gather

to trade arguments, insults and threats.

"I thought it essential that the public know this, so people can make an

informed decision when some kid on a street corner asks you, `Would you

care to take a free personality analysis?' " Lerma says.

For a long time, the church treated its Internet critics as bothersome

pests, sometimes answering their critiques, sometimes ignoring them. But

in the past week Scientology has revved up its awesome legal machinery,

launching a fierce campaign to protect its most closely guarded scripture.

A federal judge ordered the raid on Lerma's house after the church filed a

lawsuit accusing Lerma of copyright infringement and revealing trade

secrets. Church officials also paid a surprise visit to the home of a

Washington Post reporter that Saturday evening, seeking the return of

documents Lerma had sent him. And in Los Angeles, the church has persuaded

a judge to seal the court file containing the disputed Scientology

documents.

Arnie Lerma was lost without his computer. He resorted to jotting

everything on legal pads. Finally this week, he got a new laptop. And then

a sympathetic stranger mailed him a modem. But Lerma, 44, is deeply

shaken. Tears drip down his cheeks at the slightest provocation. He

descends into deep, barking sobs and cannot understand why.

He believes the church will try to harass him until he is silent. But he

says that will not happen. On the Internet, Lerma signs his postings

"Arnaldo Lerma, Clear 3502, Ex-Sea Organization Slave." It's a reference

to his old Scientology code name and his status as a mostly unpaid church

staffer. And then he writes: "I would prefer to die speaking my mind than

to live fearing to speak."

Except that when he recites the line, Lerma cannot get it out without

collapsing into spasms of sorrow.

Ruin Him Utterly'

>From the documents Lerma posted on the Internet, an oft-quoted Hubbard

directive on litigation against unauthorized use of the church's texts:

The purpose of the suit is to harass and discourage rather than to win.

The law can be used very easily to harass and enough harassment on

somebody who is simply on the thin edge anyway, well knowing that he is

not authorized, will generally be sufficient to cause his professional

decease. If possible, of course, ruin him utterly.

The church has long been quick to use the legal system against government

investigators, ex-members turned critics, and news organizations that

publish criticism of Scientology. At one point a few years ago, it had 71

active lawsuits against the IRS alone. In 1992 the church filed a $416

million libel suit -- still pending -- against Time magazine, which had

published a cover story titled "Scientology: The Cult of Greed." Earlier

this year in California it filed suit against -- and confiscated computer

disks belonging to -- another former member whom it accused of

distributing copyrighted texts. And in the past year, the church has spent

millions of dollars on an advertising blitz accusing the German government

of a "hate campaign against Scientology."

A Scientology document filed in the Los Angeles case advises church

members to discourage news reports on Scientology anywhere but in religion

pages, and to "be very alert to sue for slander at the slightest chance so

as to discourage the public presses from mentioning Scientology."

Free Speech vs. Copyright

The Church of Scientology says the Lerma case is a simple matter of trade

secrets and copyright violations. The church's unpublished, copyrighted

texts -- previously available only to church members who have paid

thousands of dollars to rise through Scientology's hierarchy of training

courses -- have been placed on the Internet, open to all.

This, Scientology lawyers argue, threatens the church's intellectual

property rights.

"Of course we want Scientology to go out as far and wide as possible,"

says Kurt Weiland, a director of the Church of Scientology International.

"There are 60 books written by the founder. There is one small section,

the upper-level materials, which are trade secrets based on our religious

understanding. A person has to have advanced in an orderly fashion,

spiritually, in order to understand its content.

"We are determined to maintain their confidentiality. We take very

forceful and elaborate steps to maintain the confidentiality. This is not

a free-speech issue. It's a copyright issue."

Scientology, which runs a celebrity outreach program and counts among its

members John Travolta, Tom Cruise and Lisa Marie Presley-Jackson, offers

to help people attain a near-god state through several levels of training

sessions. At the upper levels, church doctrine reads like a science

fiction plot.

The church believes that 75 million years ago, the leader of the Galactic

Federation, Xenu, solved an overpopulation problem by freezing the excess

people in a compound of alcohol and glycol and transporting them by

spaceship to Teegeeack -- which we know as Earth. There they were chained

to a volcano and exploded by hydrogen bombs. The souls of those dead --

"body thetans" -- are the root of most human misery to this day.

Much of Scientology's upper-level training consists of re-creations of

that galactic genocide. Weiland says most church members pay up to $20,000

to reach the final stages of the training. Critics estimate the total cost

at closer to $300,000.

It is the texts of those training sessions -- known as "Operating Thetan"

or "OT" courses -- that the church now seeks to keep secret.

In the lawsuit against Lerma, court documents unsealed Wednesday in U.S.

District Court in Alexandria contain 30 color photographs showing how

Scientology protects its sacred scriptures. Members ready to learn the

material obtain magnetized photo ID cards and sign agreements to keep the

information confidential. To see the material, they scan their ID cards to

walk through two sanitized white doors, and security guards unlock the

scriptures from cabinets where they are wired in place. Then guards escort

the members to a room where they are locked in and monitored on video

cameras.

But despite the church's precautions, the OT documents have been in a

public court file for two years, ever since they were submitted in Los

Angeles by Steven Fishman, a former Scientologist who was quoted in the

Time magazine article in 1991 and subsequently was sued by the church for

libel. The suit was dropped last year, but for more than a year, federal

court clerks say, eight people have served as a rotating guard, arriving

each morning at the L.A. courthouse to check out five volumes of the

Fishman case file and keep them all day.

"They get here when the door opens at 8:30 -- they come every day,

faithfully," says Tyrone Lawson, exhibit custodian for the U.S. District

Court clerk's office. "They never miss a day. It's like they don't want

anyone to read it."

On Monday, after a Washington Post staffer asked the clerk for the file,

one of the men challenged the clerk's right to take it to copy it,

according to Joe Nunez, another official in the clerk's office.

"He came at me [saying], `Oh, do you have the right to take this away?' "

Nunez says.

When the Post staffer approached two of the men Tuesday, they would not

say for whom they work. "We're just helping out," one said. "It's not

public," the other claimed when the staffer asked to look at the file.

Weiland confirms that the people in the clerk's office were Scientology

employees. "We took elaborate steps to assure that no one made copies of

our copyrighted material," he says. "We actually had people there."

Weiland says the only copies ever made from the court file were those made

for the Washington Post staffer.

After learning that the Post had received the documents, Scientology

lawyers renewed their efforts to seal the file in the Fishman case.

Federal Judge Harold Hupp had denied previous Scientology motions to seal

the material, but the church won a temporary sealing of the file pending

the judge's decision.

But that may not change anything, says Los Angeles lawyer Graham Berry,

who represented Fishman's co-defendant, psychologist Uwe Geertz, in the

libel case. "Now that it's all on the Internet, the genie is out of the

bottle, and no amount of pushing and shoving by the Church of Scientology

will put it back in."

Copyright lawyers say Scientology does not lose its copyright on the

sacred texts simply because they are filed in court.

"The Church of Scientology is correct," says Ilene Gotts, a partner in the

Washington office of Foley and Lardner who specializes in intellectual

property law. "The mere fact that you file something in the public domain

does not get rid of its copyright protection."

Gotts says any citizen has the right to go to a courthouse and read

anything in the files. But making photocopies of copyrighted materials

could get you in trouble, as warning signs in many libraries, for example,

make clear. And putting those documents on the Internet can further muddy

the waters, Gotts says.

"That's something courts grapple with every day," she says. "A short

passage for educational purposes is one thing, but if you're talking about

60, 80 pages, that defense is not going to work."

Clusters and Prep-Checks

If the court clerk's daily visitors made it difficult for citizens to see

the public file, some copies of the documents nonetheless got out. Lerma

says several former Scientologists passed the copies among themselves and

then gave them to him; he then used a scanner to put them onto the

Internet. Lerma also put the copies in an envelope and sent them to

Richard Leiby, a Washington Post reporter who has written frequently about

Scientology.

On the evening after the raid on Lerma's house, church lawyer Helena

Kobrin and Scientology executive Warren McShane arrived unannounced at

Leiby's home and demanded all copies he might have of the disputed

documents.

Weiland says Scientology representatives went to Leiby's home "because

Arnie Lerma gave stolen materials to Richard Leiby to hide." Lerma says he

sent the papers to the reporter in search of publicity. This week, at

Lerma's request, The Post returned the papers.

Meanwhile, the Post staffer in Los Angeles got copies of the documents

from the court file.

Most of the 103 pages of disputed texts from the Fishman file are

instructions for leaders of the OT training sessions. They are written in

the dense jargon of the church: "If you do OT IV and he's still in his

head, all is not lost, you have other actions you can take. Clusters, Prep-

Checks, failed to exteriorise directions."

Scientology's jargon is often similar to the self-actualization lingo used

by self-help groups that emerged from California in the 1960s and '70s.

Like est and Lifespring, it includes concentration exercises in which

trainees sharpen their perceptive abilities by focusing deeply on objects

or people around them. In one high-level OT session, trainees are asked to

pick an object, "wrap an energy beam around it" and pull themselves toward

the object. Another instructs the trainee to "be in the following places

-- the room, the sky, the moon, the sun."

Many excerpts from Scientology texts have been published in news accounts

over the past 20 years. What appears to be new in the Fishman documents is

a 1980 "Confidential Student Briefing" on OT-VIII. The church calls the

four-page briefing a fake.

Purportedly written by Hubbard, who died in 1986, it tells the story of

the church founder's "mission here on Earth," and warns that "virtually

all religions of any significance on this planet" are designed to "bring

about the eventual enslavement of mankind." It also states that "The

historic Jesus was not nearly the sainted figure [he] has been made out to

be. In addition to being a lover of young boys and men, he was given to

uncontrollable bursts of temper and hatred."

Ultimately, the briefing says Hubbard will return to Earth "not as a

religious leader but a political one. That happens to be the requisite

beingness for the task at hand. I will not be known to most of you, my

activities misunderstood by many, yet along with your constant effort in

the theta band I will effectively postpone and then halt a series of

events designed to make happy slaves of us all."

The text concludes, "L. Ron Hubbard, Founder." But Scientology director

Weiland says it is "a complete forgery."

Genie Out of the Bottle

Forgery or the real thing, the documents are out there. The Internet

newsgroups where the Scientology texts have been posted are among the most

popular in cyberspace, and a recent brouhaha over the erasure of Internet

messages has drawn new readers.

"I'm a computer scientist, and I knew nothing about Scientology until all

this started happening," says Dick Cleek, a professor of geography and

computer science at the University of Wisconsin Center in West Bend who

believes Scientologists are behind the erasures. "This is about the

ability of people to speak out. It's as if every letter you sent saying

`Vote Republican' got removed from the mails. . . .

"Every time they cancel one message, three more people post the

documents," says Cleek, who is also a member of the Ad Hoc Committee

Against Internet Censorship, a group of academics, computer users and

Scientology critics who want law enforcement authorities to investigate

the erased messages. "In the past, the church has harassed individuals who

dared to criticize them. Now they've attacked the Internet, and they get

people like me involved."

The church says it has never removed any messages from the Internet.

"There are thousands of messages there about Scientology," says Weiland.

"Those people were critical and obscene and we never did a thing about

it."

Weiland says people who post messages about Scientology are "just a bunch

of people of low moral standards. They don't have a life. It's really only

a handful of people, maybe 15 to 20 guys who just post, post, post, and

they just get high on each other's verbiage."

Despite the church's claim to copyright protection of its documents,

Scientology will be hard-pressed to eliminate distribution of information

already zipping around the world on the computer network, says Gotts. "The

beauty and the beast of the Internet is that information gets out

immediately," the lawyer says. The church could win every court battle,

yet still find its sacred texts flying across phone lines from Bethesda to

Beijing.

Which would suit Arnie Lerma just fine. His goal is to dissuade people

from joining Scientology by revealing the church's philosophy to be empty

and corrupt.

Lerma -- who says he left the church after leaders forced him out of a

budding romance with a daughter of the church founder -- is an angry and

sad man. He says Scientology took advantage of him as a boy of 16, luring

him into a life of virtual slavery, housing him in cold dormitories with

insufficient food. "They prey on the naive with stars in their eyes. I

just wanted to save the world."

Weiland says Lerma left because "Scientology has certain ethical

standards. And Arnie Lerma was not able to live up to these standards and

therefore decided to leave. There were problems with honesty."

"Ultimately," Weiland says, "his motivation is money." The director adds

that Lerma never asked Scientology for money. "Not yet," he says.

Lerma contends he has violated no copyright, and intended only to

distribute portions of the court file, "a public court record that I had a

public duty to make available to the people because they were keeping it

secret."

Arnie Lerma is a man given to causes. For years, he sought solutions

through Scientology. More recently, he became intensely active in Ross

Perot's abortive presidential campaign. Then he dived into efforts to

unmask what he calls Perot's "terrible misdeeds." Now he has turned to

Scientology once more.

Or, rather, against it. He says he does not seek revenge, only justice. He

says that after he left the church, he went through a post-traumatic

stress reaction, then through denial and, finally, a "reawakening."

Lerma lights up another Marlboro. He says he's smoking too much now. Every

time the phone rings, he jumps up off the couch. Every time there's a

knock at the door, he glances around the room.

Suddenly, he recalls the moment in 1977 when he called his mother in

Georgetown and asked her to take him away from Scientology. "I said, `Mom,

I want to come home now and see if I can make life make some sense,

because it surely doesn't right now.' "

And now, 18 years later, as Lerma says those words once more, he rolls

over on his couch, drops his cigarette, and sobs until he laughs.

Special correspondent Kathryn Wexler in Los Angeles and staff writer Lan Nguyen in Alexandria contributed to this report. Copyright 1995 The Washington Post Any amounts gifted for this cause will be used to continue to spread the word about the true nature of this threat, and provide assistance to others who have risked lives, family and career and the intended ‘death by stress’ litigation tactics to bring you the truth - please make copies and pass this on... Arnaldo Pagliarini Lerma - 6045 N 26th Road, Arlington Virginia 22207 - (703) 241 1498